If there is a distinguishing feature of Mark’s gospel (you

might even call it Mark’s signature), it is the word “immediately”. You find it

peppered all through its sixteen chapters. When Jesus is baptized in the Jordan,

he immediately comes up out of the water (1:10). Then, immediately the Spirit drives

him out into the wilderness (1:12). Jesus calls Simon and Andrew to become fishers

of people and immediately they drop their nets and follow him (1:18). Jesus and

his disciples go to Capernaum and immediately on the Sabbath he goes to the

synagogue and teaches (1:21). Then, immediately, a man with an unclean spirit

begins shouting and Jesus rebukes it (1:23). Immediately after that, Jesus goes

to the home of Simon and Andrew and heals Simon’s mother-in-law, who is sick

with a fever (1:29). A leper begs Jesus to make him clean. Jesus touches him

and says, “Be clean,” and immediately the leprosy leaves him (1:40-43). At this

point we haven’t even left the first chapter! In all, we find the word in

forty-two places—ten times in the first chapter alone.

Thus it seems that throughout Mark’s gospel, far more than

the other three, there is always a sense of motion—not of hurry, not of things

moving more quickly than they ought or being out of control, but always moving.

The final point at which we encounter the word “immediately” is in the opening

verse of this morning’s Gospel reading. Unfortunately you won’t see it in very

many of our English translations. However, rendered literally, Mark 15:1 sounds

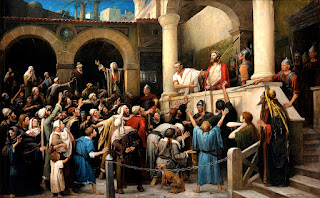

like this: “And immediately, very early in the morning, the chief priests, with

the elders and scribes, and the whole council, held a consultation…” And that

is the last time we hear it. Suddenly, it seems, time slows down.

The foreknowledge of God

Mark compresses three years of Jesus’ life into fourteen

chapters. He does not even give any account of Jesus’ birth. Now he devotes an

entire chapter to just nine hours. I find myself asking, why is this so? One

idea that comes to my mind takes me back many years ago to a winter morning

when I was driving on the open freeway out in the countryside. Suddenly, a considerable

distance away, I could see that all the traffic had come to a halt. I tapped

the brakes and realized that I had no control whatever over my car. I was

driving on black ice. I put the car into neutral and tried to steer it gently to

the side of the road. But nothing I did had any effect. Unable to do anything

to prevent whatever was going to happen, I found myself beginning to feel more

like a helpless observer than a driver. As my car glided toward the vehicles

ahead of me, I had an eerie sense that time had slowed down. The interval

between first spotting the stopped cars far ahead and when I finally crashed

into the back of a school bus that had gone off the road seemed not like the

few seconds that it was, but minutes.

So I ask myself, is this the way that it was for Jesus’

disciples? As events took their course on that fateful Friday morning, there

was a sense of inevitability, that now there was nothing they could do to

intervene in the series of events that was unfolding before them. Looking back

on it, we can say they should have known. On more than one occasion, going all

the way back to the time when Peter had proclaimed him the Messiah, Jesus had

warned them that “the Son of Man must undergo great suffering, and be rejected

by the elders, the chief priests, and the scribes, and be killed…” (Mark 8:32).

At what should have been a celebratory event—the Passover meal—there had been

the sadness that had hung over everything like an ominous cloud, when Jesus had

taken the bread and said, “This is my body, broken for you,” and the wine with

the words, “This is my blood, poured out for you and for many.” That same night,

as Judas Iscariot entered the Garden of Gethsemane with the soldiers and a band

of ruffians, who dragged Jesus away to the court of the high priest, they must

have known in their hearts that things had gone beyond the point of no return. All

that was left for them to do was to look on helplessly as Jesus was carried

away to be crushed by the unstoppable wheel of fate.

He was oppressed, and he was afflicted,

yet he did not open his mouth;

like a lamb that is led to the slaughter,

and like a sheep that before its shearers is silent,

so he did not open his mouth.

By a perversion of justice he was taken away.

Who could have imagined his future?

For he was cut off from the land of the living,

stricken for the transgression of my people. (Isaiah 53:7-8)

yet he did not open his mouth;

like a lamb that is led to the slaughter,

and like a sheep that before its shearers is silent,

so he did not open his mouth.

By a perversion of justice he was taken away.

Who could have imagined his future?

For he was cut off from the land of the living,

stricken for the transgression of my people. (Isaiah 53:7-8)

What the disciples did not know, what they could never have

conceived at the time, was that things were not out of control at all—that what

was unfolding was not evil running unchecked, but the long-awaited plan of a

loving Father. “It was the will of the Lord to crush him; he has put him to

grief…” wrote Isaiah centuries before (Isaiah 53:10). Or not many days later,

as Peter himself would soon recognize and proclaim, “This man [was] handed over

… according to the deliberate plan and foreknowledge of God” (Acts 2:23).

O the depth of the riches and wisdom and knowledge of God!

How unsearchable are his judgments and how inscrutable his ways!

For who has known the mind of the Lord?

Or who has been his counselor? (Romans 11:33-34)

How unsearchable are his judgments and how inscrutable his ways!

For who has known the mind of the Lord?

Or who has been his counselor? (Romans 11:33-34)

A fact of history

Let’s stop there for a moment. For I believe that there may

be a second reason why time slows down at this point in Mark’s gospel. It stems

from a curious incident the night before, as Jesus is being led away from the

Garden of Gethsemane, and of the four gospels it is found only in Mark’s

account. In chapter 14, verses 51 and 52, we are told about a young man who had

been following along behind Jesus and the disciples wearing nothing but a linen

cloth. The guards tried to apprehend him, but all they managed to do was to grab

hold of the cloth and off he ran, naked, into the dark.

Practically ever since people have been asking, could this

have been Mark? After all, it is not unlikely that the upper room where the

last supper took place was in the home of Mark’s mother, Mary. Could he have

sneaked out of the house and followed Jesus and the disciples across the Kidron

Valley to the garden? Added to that, Mark would have been a very young man,

likely not even have reached puberty, so he would not have been regarded as a

threat by the authorities. Could it be then that what we have from this point

on in the gospel is not a second-hand report of the events, but an actual

eyewitness account? I grant that all of this is to some extent speculation, but

it might explain why Mark goes into such detail at this point.

He carefully notes times—a detail we don’t find anywhere

else in his gospel. At nine o’clock Jesus is crucified. At noon darkness

shadows the whole land. At three o’clock Jesus cries out, “Eloi, Eloi, lema

sabachthani?” and then breathes his last. Why all the detail? Because Mark

wants to make sure that we know that what we are reading about are actual

events. The nails that pierced Jesus’ hands were hard iron. The wood on which he

hung was rough and splintered. The pain that tormented his naked body ran

through every nerve.

As we read the account of the Passion, we need to remember

that this is not just a story, a myth that has been devised or a legend that

has been passed down. What we commemorate over this Holy Week are actual

events, testified to by eyewitnesses, that took place in real time. “For I

handed on to you as of first importance what I in turn had received,” wrote the

apostle Paul less than twenty years later, “that Christ died for our sins in

accordance with the Scriptures” (1 Corinthians 15:3). “What we have heard,

what we have seen with our eyes, what we have looked at and touched with our

hands,” wrote St John, “we declare to you” (1 John 1:1). The crucifixion

was a real event. The cross is real.

The fulcrum of eternity

There is another reason that occurs to me as to why Mark

slows down at this point. Picture yourself on a train, speeding across the

countryside. The train begins to decelerate. Then slowly, its brakes squealing

and sparks flying from its wheels, it comes to a halt. You have reached your

destination.

It is at the cross that the gospel also reaches its

destination. It is at the cross that everything stops. All creation holds its

breath and gasps as the Lamb of God breathes his last and bows his head. And a

centurion, who knows nothing of the Bible, nothing of God’s centuries-long

pursuit of his people, nothing about Jesus, looks up and exclaims, “Truly this

man was the Son of God!” For the cross was Jesus’ destination also. “The hour

has come for the Son of Man to be glorified.” “And I, when I am lifted up from

the earth, will draw all people to myself” (John 12:23,32).

The cross is the fulcrum on which the destiny, not just of

humankind, but of the entire universe, turns. “Through him God was pleased to

reconcile to himself all things, whether on earth or in heaven, by making peace

through the blood of his cross” (Colossians 1:20). It is on the cross that sin

is canceled, the powers of evil overthrown, the tragic chain of events that can

be traced all the way back to the Garden of Eden is reversed, and death becomes

the gate to eternal life.

But we have not let the cross do its work until what is the

fulcrum of eternity becomes the fulcrum of our lives as well. We can accept it

as a fact of history. We can wonder at it as the ultimate act of sacrifice by a

loving Savior. But until we bow before it and receive the grace and forgiveness

that Jesus has wrought for us there, it can only be a symbol, a distant event shrouded

by the mists of the past.

“I have been crucified with Christ,” wrote the apostle Paul,

“and it is no longer I who live, but it is Christ who lives in me. And the life

I now live in the flesh I live by faith in the Son of God, who loved me and

gave himself for me” (Galatians 2:20). The

challenge of Holy Week, the challenge of the cross, is to allow what Jesus has

done there to become a present reality for us, to accept in humble gratitude

the terrifying but awesome truth that it was for me and for my sins that

Jesus shed his blood and gave himself over to death. He died so that I might live…

What more is there to say, except to pray? And for that I

would like to use the words of Isaac Watts. If you know them, perhaps you would

like to say them with me.

Forbid it, Lord, that I should boast,

save in the death of Christ my God:

all the vain things that charm me most,

I sacrifice them to his blood.

save in the death of Christ my God:

all the vain things that charm me most,

I sacrifice them to his blood.