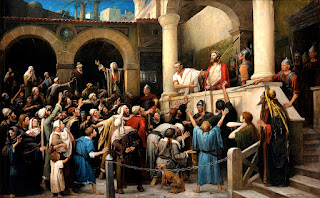

For people who believe in the basic decency and nobility

of mankind, reading Mark’s account of the trial of Jesus must be a painful

experience. “Why,” they must ask, “wasn’t there someone to stand up and shout,

‘He’s innocent!’ for all to hear?” “Why wasn’t there anybody in that crowd of

people who could have stood up and, in the name of humanity, spoken for Jesus?

He might not have saved him from death. Indeed, he might have been crucified

beside him. But why didn’t somebody do something?"

The sad fact of the matter is, though, that nobody did anything.

There was not one finger lifted by anyone to prevent Jesus from taking that

road which led to the cross. The silence of that day speaks with its own

peculiar eloquence to us today. As we examine the trial of Jesus, we begin to

see just how powerful the opposition to him was. The judgment had already been

made long before the trial began. Mark writes that “the chief priests and the

council sought testimony against him to put him to death”. This certainly was

not a trial as we generally understand it. Rather, it was an excuse for a

trial—a performance—to give the cruel acts of these people the appearance of

justice.

Yet there is another sense in which that procedure was very

much a trial—not of Jesus, but of the people who were condemning him. Jesus’

calmness under great pressure and the emotional and irrational behavior of the

high priest suggest to us that it was not Jesus at all who was on trial, but

the motives and actions of his prosecutors.

Who was on trial that evening? Not Jesus, but the rest of

mankind. Who was found guilty? Not Jesus, for his innocence was obvious from

the very beginning. Rather, the guilty party in this trial were all the people

who condemned him: the chief priests and the council whose plan it was to put

him to death from the very beginning; the false witnesses, brought in to tell

lies about a man they hardly knew; the bystanders, who spat on him and struck

him; the guards who beat him; and Peter, who in a moment of weakness denied him

three times.

No one stood up for Jesus at the trial because no one wanted

to stand up for him. That sounds like a terrible condemnation of the people

present. Yet I can say it, not out of any feelings of self-righteousness, or

any knowledge that I would have been the one to stand in Jesus’ defense. Quite

the contrary, I am convinced that, left to myself, I would have been as

condemnatory as any of them. The reason why no one spoke forth at the trial of

Jesus, and why, I believe, even today if that scene were re-enacted nobody

would object, is that basically, when left entirely to ourselves, we are all,

each one of us, at enmity with God. That is not to say that we cannot love God

with heart, mind, soul and strength as Jesus has commanded us. Rather, when

left to our natural inclinations, we do not want to.

We are like Jonah, the prophet. When God commanded him to go

to Nineveh to cry against the wickedness of the people there, Jonah immediately

went in the opposite direction, to Tarshish, to flee from the burdensome task

which the Lord had given him. We are like the rich young ruler who came to

Jesus. He would gladly have followed Jesus had he not been told to go and sell

all he had and give it to the poor. The willing disciple went away sorrowful,

for he was very rich. In each case, life could be much more comfortable without

God—and the demands and responsibilities which he places upon us.

This natural resistance which we all have to the things of

God and the ways of God built up to a kind of crescendo at the trial of Jesus.

The chief priests and the council were anxious to get rid of Jesus, for the

power and authority they received through their form of religion by ritual and

decree would disappear if Jesus’ more basis teachings of love of God and

neighbor took hold of people. Life for them was made easy by religious laws,

which sheltered them from the real demands of God; and Jesus’ teachings cut at

the very root of that way of life.

When they finally condemned him, he was turned over to

guards, who, in Mark’s words, “received him with blows”—not because he had done

anything to warrant them, but because for them it was easier than taking him

seriously, than treating him like a human being. To do so would have caused

them to crack under the violent and impersonal style of life forced upon them

by necessity. To understand their captives as any more than animals would be to

reveal their own weakness and vulnerability.

Not far away there was Peter, who only shortly before had

sworn his intention to die for Jesus, if need be. Now even he could not admit

to a casual acquaintance with Jesus before a harmless servant girl. In the past

few hours he had seen all his glorious dreams crushed to powder by Jesus’

arrest and trial. He had invested a great deal of himself in Jesus over the

past years, and now it was lost. He was not willing to surrender what little of

himself he had left, even if it was for God. He had lost too much already.

Thus, in many forms, man’s natural rejection of God in every

age found a concrete expression in the unjust trial and cruel execution of

Jesus. And we may ask ourselves, “Would things be different today?” “How long

would Jesus last amongst the people of our age, and amongst us?” “What in us would

cause us to reject Jesus?”

Are we like the chief priests, preferring to cling to the

rigid statutes of an ethical religion, rather than encounter the living God?

Are we like Jesus’ guards, failing to see the people around us as people

because that may threaten our whole way of life? Or are we like Peter, who knew

the joy of following Jesus, but in a difficult situation could not identify

with him because he was not willing to accept the cost? Like me, you may see

something of yourself in each of these people. Yet the question of how each of

us rejects God is really one between ourselves and him.

We do not ask it in order to fill ourselves with manufactured

feelings of guilt and self-condemnation. The story of the cross is not merely

the story of man’s rejection of God. It is also the story of God’s forgiveness

for men. Our own guilt as we stand before that cross should lead us, not to run

from God in shame, but to run to him, and to the Christ who said, “Father,

forgive them…”

There were no heroes at Jesus’ trial—people quick to rush to

his defense. There are no heroes of the Christian faith—only saints, sinners

forgiven and empowered by God to live for him. They are people like Peter and

like you and like me, whom God takes in our weakness and uses in his strength.

God grant us that strength which we do not have of ourselves, the strength to

submit to and live for him.

No comments:

Post a Comment